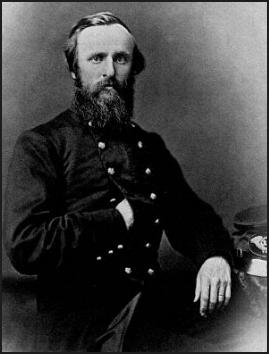

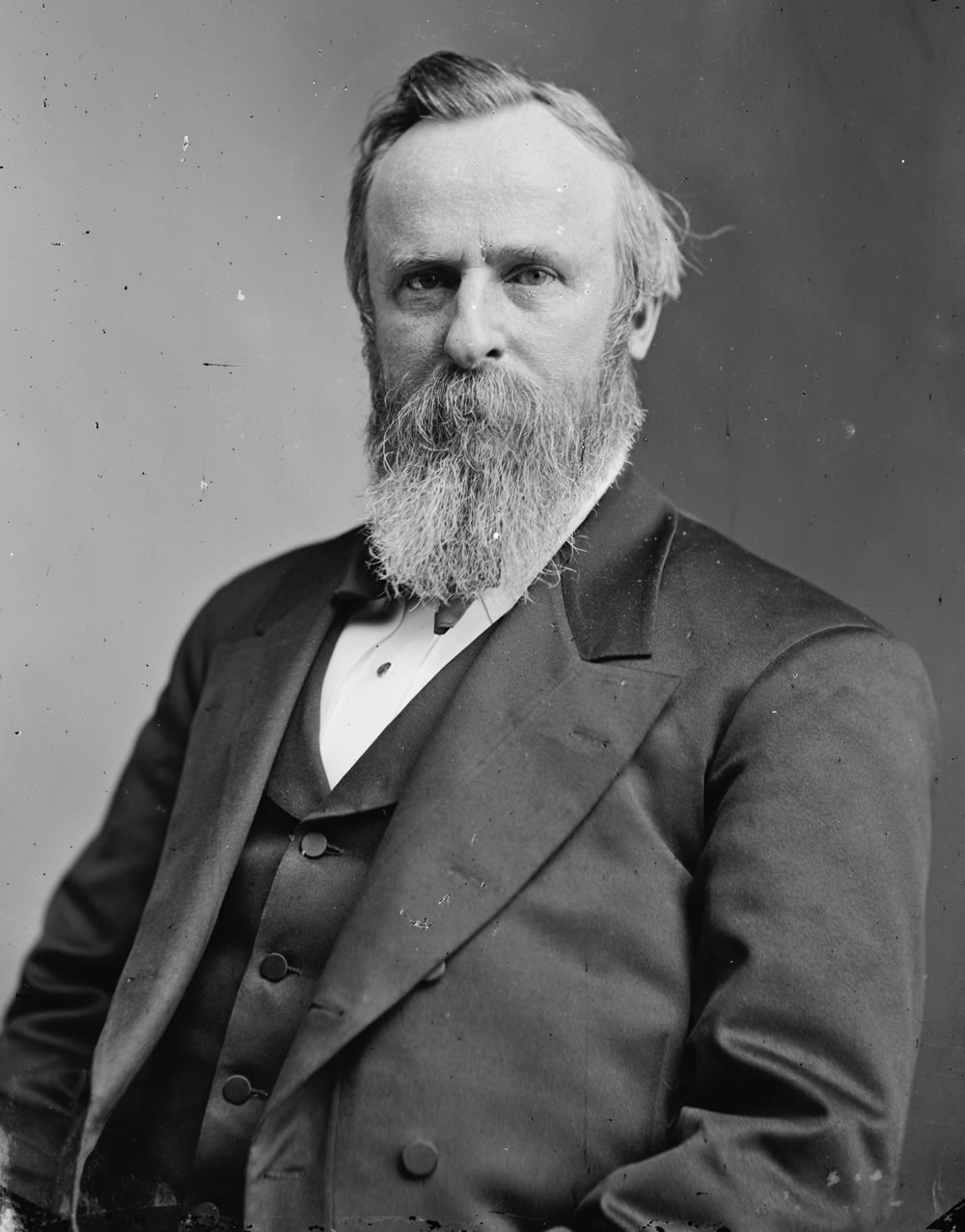

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes (right), a Congressman in the US House of Representatives, twice the Governor of Ohio, and the 19th President of the United States, but those are not the reasons that we are taking a look at him...

Nope, we have a very different reason for being interested in Rutherford Birchard Hayes. During the American Civil War, the future President served as an officer in the Union Army, and seemed to have a penchant for getting shot, and he was a fearless leader in the heat of battle.

Hayes was born on October 4, 1822, in Delaware, Ohio. He went to college in Ohio and then went to law school at Harvard. He spent some time as a fairly unsuccessful small town lawyer before heading to Cincinnati, Ohio. There he had greater success as a lawyer, and his involvement in the Republican Party there led him to be elected twice as the Cincinnati City Solicitor.

When the south began to secede in late 1860 and early 1861, Hayes expressed the feeling that war might be unnecessary, and it might be just as well for the Union to "let them go." However, when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, he changed his mind and volunteered to fight, and the Governor of Ohio made Hayes a Major in the 23rd Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

Initially, Rutherford B. Hayes was stationed in West Virginia, and saw no action in any major battles. He and his regiment were in a number of skirmishes, however, and Hayes began to show himself as a very good leader, gaining the trust of his men. As one biographer later wrote, "On several occasions he had narrow escapes from death; and at one time he fell into an ambuscade, from which the bullets hissed all about him, the bushwhackers having a cross-fire upon him at short range. But he escaped without injury, exhibiting a coolness which increased his popularity among his men as a military leader." Hayes soon saw promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and eventually to Colonel of the 23rd Ohio.

Civil War Wounds

During this time, Rutherford B. Hayes (left) led the 23rd Ohio on a number of raids against the Confederates in West Virginia. In one of these raids, Hayes received his first wound. It was a knee wound which he did not allow to keep him from active duty.

During the summer of 1862, Hayes and the 23rd Ohio were ordered East to Washington D.C. to join General John Pope and the Army of the Potomac at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Hayes and his men arrived in time to see the Union troops retreating back to Washington.

Hayes and his men then joined the Army, now under the command of General McClellan, in the pursuit of General Lee and the Confederate Army as they headed into Maryland. As Lee continued his advance through Maryland, he left behind a small force to guard the passes around South Mountain. This force, largely under the command of General D. H. Hill, was tasked with slowing down the Union's pursuit.

On September 14, 1862, Union forces under General McClellan attacked along three passes to start the Battle of South Mountain. Lieutenant Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes and the men of the 23rd Ohio led the Union attack at Fox's Gap. During this battle Hayes received his second, and most serious, wound of the Civil War. Here is an entry from his journal describing the action that day (especially note the fact that he directs his men while lying wounded between the lines during the heat of battle):

"At 7 A. M. we go out to attack. I am sent with [the] Twenty-third up a mountain path to get around the Rebel right with instructions to attack and take a battery of two guns supposed to be posted there. I asked, "If I find six guns and a strong support?" Colonel Scammon replies, "Take them anyhow." It is the only safe instruction.

... Started a Rebel picket about 9 A. M. Soon saw from the opposite hill a strong force coming down towards us; formed hastily in the woods; faced by the rear rank (some companies inverted and some out of place) towards the enemy; pushed through bushes and rocks over broken ground towards the enemy; soon received a heavy volley, wounding and killing some. I feared confusion; exhorted, swore, and threatened. Men did pretty well. Found we could not stand it long, and ordered an advance. Rushed forward with a yell; enemy gave way. Halted to reform line; heavy firing resumed.

I soon began to fear we could not stand it, and again ordered a charge; the enemy broke, and we drove them clear out of the woods. Our men halted at a fence near the edge of the woods and kept up a brisk fire upon the enemy, who were sheltering themselves behind stone walls and fences near the top of the hill, beyond a cornfield in front of our position. Just as I gave the command to charge I felt a stunning blow and found a musket ball had struck my left arm just above the elbow. Fearing that an artery might be cut, I asked a soldier near me to tie my handkerchief above the wound. I soon felt weak, faint, and sick at the stomach. I laid [lay] down and was pretty comfortable. I was perhaps twenty feet behind the line of my men, and could form a pretty accurate notion of the way the fight was going. The enemy's fire was occasionally very heavy; balls passed near my face and hit the ground all around me. I could see wounded men staggering or carried to the rear; but I felt sure our men were holding their own. I listened anxiously to hear the approach of reinforcements; wondered they did not come.

I was told there was danger of the enemy flanking us on our left, near where I was lying. I called out to Captain Drake, who was on the left, to let his company wheel backward so as to face the threatened attack. His company fell back perhaps twenty yards, and the whole line gradually followed the example, thus leaving me between our line and the enemy. Major Comly came along and asked me if it was my intention the whole line should fall back. I told him no, that I merely wanted one or two of the left companies to wheel backward so as to face an enemy said to be coming on our left. I said if the line was now in good position to let it remain and to face the left companies as I intended. This, I suppose, was done.

The firing continued pretty warm for perhaps fifteen or twenty minutes, when it gradually died away on both sides. After a few minutes' silence I began to doubt whether the enemy had disappeared or whether our men had gone farther back. I called out, "Hallo Twenty-third men, are you going to leave your colonel here for the enemy?" In an instant a half dozen or more men sprang forward to me, saying, "Oh no, we will carry you wherever you want us to." The enemy immediately opened fire on them. Our men replied to them, and soon the battle was raging as hotly as ever. I ordered the men back to cover, telling them they would get me shot and themselves too. They went back and about this time Lieutenant Jackson came and insisted upon taking me out of the range of the enemy's fire. He took me back to our line and, feeling faint, he laid me down behind a big log and gave me a canteen of water, which tasted so good. Soon after, the fire having again died away, he took me back up the hill, where my wound was dressed by Dr. Joe."

After his wound was dressed, Lieutenant Colonel Hayes was taken into a nearby town where he spent a considerable time recuperating. At times, he thought his arm would need to be amputated, and once, out of fear that infection was setting in, he even tried to convince his doctor to remove the arm. His doctor thought he could save the arm and convinced Lieutenant Colonel Hayes to let him try. The doctors efforts were successful, and after a few weeks Lieutenant Colonel Hayes was back with his men.

Another interesting excerpt from Lieutenant Colonel Hayes's entry on the Battle of South Mountain mentions his interaction with a Confederate soldier while they both lay wounded, "... I omitted to say that a few moments after I first laid [lay] down, seeing something going wrong and feeling a little easier, I got up and began to give directions about things; but after a few moments, getting very weak, I again laid [lay] down. While I was lying down I had considerable talk with a wounded [Confederate] soldier lying near me. I gave him messages for my wife and friends in case I should not get up. We were right jolly and friendly; it was by no means an unpleasant experience."

After he was recovered, Hayes and his men saw more action throughout 1863 and 1864, playing an important part in the Valley Campaigns of 1864 under General Philip Sheridan. During this time, Hayes, serving with characteristic skill and bravery, managed to get wounded twice more. Late in 1864, in recognition of his outstanding service, Hayes received the rank of Major General.

While he was not the most injured officer of the American Civil War, Rutherford B. Hayes suffered his share of battlefield wounds. All told, he was wounded in battle on four separate occasions, and also had four horses shot from under him. His sacrifice and bravery did not go without notice. As General Ulysses S. Grant later wrote, "[h]is conduct on the field was marked by conspicuous gallantry as well as the display of qualities of a higher order than that of mere personal daring."

Return to Political Life

While he was still off fighting, Cincinnati Republicans nominated Rutherford B. Hayes for a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives in the 1864 election. Although he accepted the nomination, Hayes refused to return home to campaign, saying, "An officer fit for duty who at this crisis would abandon his post to electioneer for a seat in Congress ought to be scalped. " Rather than campaigning, Hayes wrote open letters to the voters outlining his political beliefs, and he won the election by 2,400 votes over the incumbent Democrat.

In 1867, Hayes resigned his seat in congress to run for Governor of Ohio. He won by a narrow margin. At the end of his term Hayes declined to seek reelection.

When his term was up, in 1872, Hayes intended to retire from politics; but the Republicans nominated him for Governor again in 1875, and he accepted. He won the election and began his second term as Governor in 1876.

Later that same year, the Republican National Convention nominated him as the Republican candidate for President.

The Democratic nominee was the Governor of New York, Samuel J. Tilden. It was a very close campaign, and as results started coming in on election night, Hayes believed he had lost and went to bed.

Indeed, he did lose the popular vote by roughly a quarter million votes, but the electoral college results were not so clear. Due to fraud committed by both parties in Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana, the results in those states were unclear. Both parties insisted that their candidate had won, but there was no clear resolution to the problem.

Finally, a bi-partisan election commission was formed to decide which candidate would receive the electoral votes from the disputed states. At this point, Tilden had secured 184 electoral votes and Hayes had 165. With 20 votes up for grabs, 185 votes were needed to win the election. The election commission was composed of eight Republicans and seven Democrats. Unsurprisingly, the commission voted 8-7 to give all 20 electoral votes to Hayes, thus securing Hayes election as President of the United states.

The Democrats filibustered the acceptance of the election commission's findings until they secured a number of concessions from the Republicans. Among those concessions was the withdrawal of troops from the south and the end of Reconstruction. On March 2, 1877, two days before Inauguration Day, Rutherford B. Hayes was finally confirmed as President.

Hayes never sought reelection. Instead, he introduced a plan to limit Presidents to one six year term, but his effort failed.

Rutherford B. Hayes, was an untrained officer who rose through the Union ranks thanks to his courage under fire, leadership in the face of danger, and ability to withstand multiple wounds. These characteristics endeared him to his men, and later endeared him to voters, launching his successful political career. All told, Rutherford B. Hayes was a true American Civil War hero.

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.