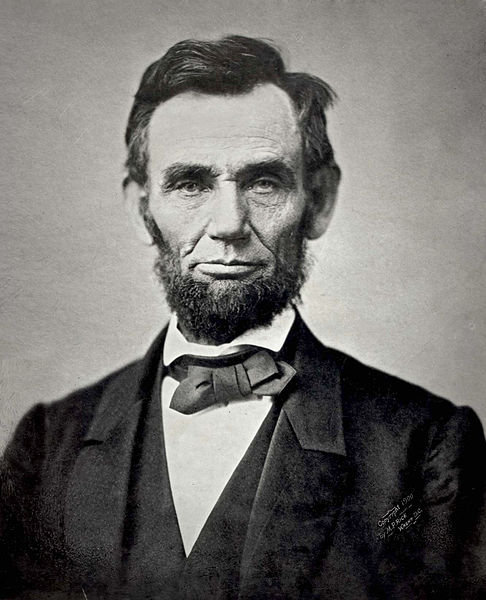

Attempted Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On a dark summer night, an unknown assassin took aim at the head of the President of the United States and pulled the trigger. Something spoiled his aim...

Perhaps it was too dark for the assassin to properly discern his target, perhaps the magnitude of what he was doing caused him to lose his nerve and become unsteady. Whatever the reason, the shot went high. The bullet passed harmlessly through the President's hat, knocking it to the ground; and the President rode frantically to safety.

The President was Abraham Lincoln, but to this day, no one knows who the would-be assassin was.

The attempted assassination of Abraham Lincoln took place in August of 1864, roughly eight months before John Wilkes Booth would assassinate Lincoln at Ford's Theater. Lincoln was riding to the Soldiers' Home outside of Washington D.C., where the President and his family stayed to escape the heat during the summer, when the attempt took place.

The following account from Private John W. Nichols appeared in the April 6, 1887 issue of the New York Times after originally appearing in the Wheeling Register (West Virginia):

One night about the middle of August Mr. Nichols was doing sentinel duty at the large gate to the grounds of the home. About 11 o'clock he heard a rifle shot, and shortly afterward Mr. Lincoln dashed up to the gate on horseback. The President was bareheaded, and as he dismounted he said, referring to his horse; " He came pretty near getting away with me, didn't he? He got the bit in his teeth before I could draw the rein." Mr. Nichols asked him where his hat was, and he replied that somebody had fired a gun off at the foot of the hill, and that his horse had become scared and jerked his hat off.

"Thinking the affair rather strange," said Mr. Nichols, "a corporal and myself went down the hill to make an investigation. At the intersection of the driveway and main road we found the President's hat — a plain silk one — and upon examining it we discovered a bullet hole through the crown. The shot had been fired upward, and it was evident that the person who fired the shot had secreted himself close by the roadside. The next day I gave Mr. Lincoln his hat and called his attention to the bullet hole. He remarked rather unconcernedly, that it was put there by some foolish gunner and was not intended for him. He said, however, that he wanted the matter kept quiet, and admonished us to say nothing about it. We felt confident that it was an attempt to kill him, and a well nigh successful one, too. The affair was, of course, kept quiet in compliance with the President's request. After that the President never rode alone."

Private Nichols' story was corroborated by President Lincoln himself, who told the story to his friend, Ward Hill Lamon, shortly after it took place. Lamon later recounted the story Lincoln told in his book Recollections of Abraham Lincoln :

Lincoln Tells the Story...

"I have something to tell you!" and after we had entered his office he locked the doors, sat down, and commenced his narration. (At this distance of time I will not pretend to give the exact words of this interview, but will state it according to my best recollection.) He said: "You know I have always told you I thought you an idiot that ought to be put in a strait jacket for your apprehensions of my personal danger from assassination. You also know that the way we skulked into this city, in the first place, has been a source of shame and regret to me, for it did look so cowardly!"

To all of which I simply assented, saying, "Yes, go on."

"Well," said he, "I don t now propose to make you my father-confessor and acknowledge a change of heart, yet I am free to admit that just now I don't know what to think..."

He paused; I requested him to go on, for I was in painful suspense. He then proceeded.

"Last night, about 11 o'clock, I went out to the Soldiers' Home alone, riding Old Abe, as you call him [a horse he delighted in riding], and when I arrived at the foot of the hill on the road leading to the entrance of the Home grounds, I was jogging along at a slow gait, immersed in deep thought, contemplating what was next to happen in the unsettled state of affairs, when suddenly I was aroused - I may say the arousement lifted me out of my saddle as well as out of my wits - by the report of a rifle, and seemingly the gunner was not fifty yards from where my contemplations ended and my accelerated transit began. My erratic namesake, with little warning, gave proof of decided dissatisfaction at the racket, and with one reckless bound he unceremoniously separated me from my eight-dollar plug-hat, with which I parted company without any assent, expressed or implied, upon my part. At a break-neck speed we soon arrived in a haven of safety. Meanwhile I was left in doubt whether death was more desirable from being thrown from a runaway federal horse, or as the tragic result of a rifle-ball fired by a disloyal bushwhacker in the middle of the night."

...He seemed to want to believe it a joke. "Now," said he, "in the face of this testimony in favor of your theory of danger to me, personally, I can't bring myself to believe that any one has shot or will deliberately shoot at me with the purpose of killing me; although I must acknowledge that I heard this fellow's bullet whistle at an uncomfortably short distance from these headquarters of mine. I have about concluded that the shot was the result of accident. It may be that some one on his return from a day's hunt, regardless of the course of his discharge, fired off his gun as a precautionary measure of safety to his family after reaching his house." This was said with much seriousness.

He then playfully proceeded: "I tell you there is no time on record equal to that made by the two Old Abes on that occasion. The historic ride of John Gilpin, and Henry Wilson's memorable display of bareback equestrianship on the stray army mule from the scenes of the battle of Bull Run, a year ago, are nothing in comparison to mine, either in point of time made or in ludicrous pageantry. My only advantage over these worthies was in having no observers. I can truthfully say that one of the Abes was frightened on this occasion, but modesty forbids my mentioning which of us is entitled to that distinguished honor. This whole thing seems farcical. No good can result at this time from giving it publicity."

Valuable Lessons Ignored

In his telling of the story, Lincoln makes mention of the fact that he had to, before his inauguration, take measures to evade a possible assassination plot that had been uncovered by Timothy Webster.

Despite that clear signal of danger, Lincoln could still be found riding several miles, alone, at night, nearly four years later.

It is even more odd that, after having a bullet go through his hat, Lincoln lay the blame on a careless hunter. It really makes no sense.

What I do know is that despite the urging of friends, like Ward Hill Lamon (left), Lincoln refused to have a permanent bodyguard.

It would seem that after more than one example that there were individuals willing to assassinate him, Lincoln should have been wise enough to take greater precautions; but as Lamon relates, Lincoln did not:

"It was impossible, however, to induce him to forego these lonely and dangerous journeys between the Executive Mansion and the Soldiers Home. ...he often eluded our vigilance; and before his absence could be noted he would be well on his way to his summer residence, alone, and many times at night."

One has to wonder what might have been different if Lincoln had accepted the suggestions of men like Lamon... Perhaps precautions could not have been taken that would have prevented Booth from succeeding...

...that is a question that can never be answered. Much like the fact that we will probably never know who pulled the trigger on that August evening in 1864...

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.