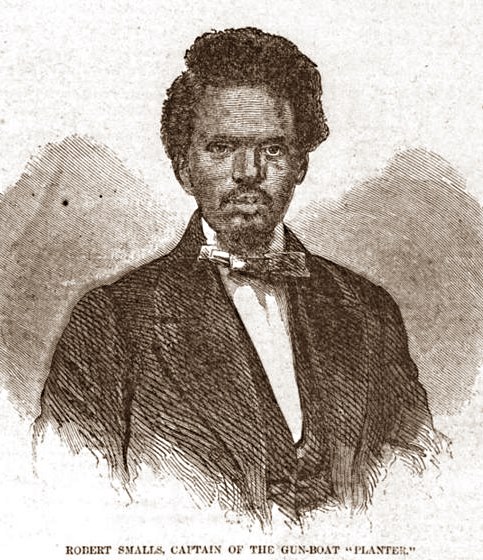

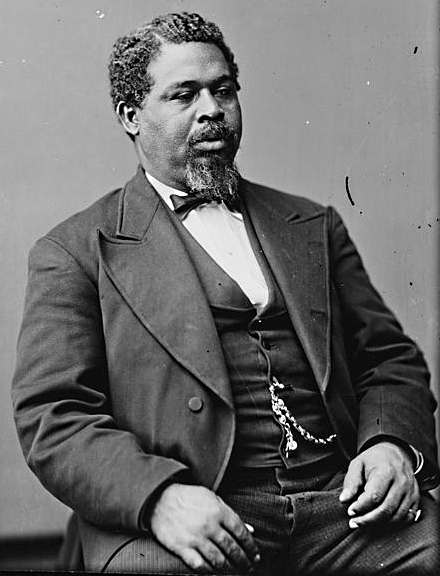

Robert Smalls

- Written by Mark Weaver

"On May 13, 1862, the Confederate steamboat Planter, the special dispatch-boat of General Ripley, the Confederate post commander at Charleston, S. C, was taken, by Robert Smalls ... from the wharf at which she was lying, carried safely out of Charleston Harbor, and delivered to one of the vessels of the Federal fleet then blockading that port..."

Thus begins Report Number 1887 of the Committee on Naval Affairs, filed during the second session of the 47th Congress of the United States. This introduction only hints at the daring nature of what Robert Smalls pulled off during the early hours of that May morning in 1862. To get a better idea of what took place, lets back up and take a look at who Robert Smalls was.

Robert Smalls was born a slave in April of 1839 in Beaufort, South Carolina. When Robert was 12, his master, Henry McKee, started hiring him out as a tradesman in Charleston. He started out working in a hotel, later he got a job as a lamplighter for the city. Finally, he began working on the docks, and discovered a love of the sea.

Robert soon started working on harbor boats, learning about rigging and sail making. He showed a natural aptitude for navigation, and before long he was working as a wheelman (the title given to black pilots at the time) in Charleston Harbor, and all along the coastal waters of South Carolina.

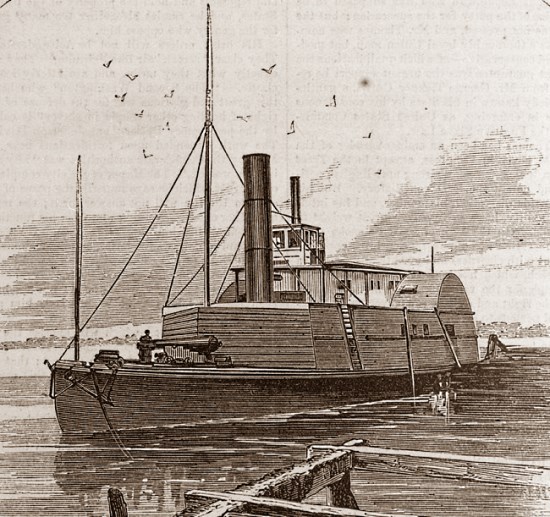

In 1861, at the beginning of the war, Robert Smalls was assigned as wheelman aboard the Confederate gunboat Planter. In this role, he piloted the Planter (under command of a white Captain and two other white officers) around the harbor, helping to lay mines and other obstructions in order to defend the city against attack from the blockading Union fleet.

During this time, Robert had gotten married (in 1856) to Hannah Jones, and they had two children: Elizabeth Lydia (1858) and Robert Jr. (1861). Hannah and the children were owned by a different master, and even though he was trying to save up to buy their freedom, the situation seemed hopeless.

Until he had an idea...

The Escape

Who knew Charleston harbor better than him? Who could sail the Planter better than him? Few if any, was the answer to both of those questions. So, Robert (just 23 years old at the time) began plotting with the other members of the Planter's crew (all of whom were also slaves) how they might sail the Planter to freedom.

They soon had a plan in place, and on the night of May 12, 1862, Robert decided to put it into action. The Committee on Naval Affairs tells us what took place:

"That night all the officers went ashore and slept in the city, leaving on board a crew of eight men, all colored. Among them was Robert Smalls, who was virtually the pilot of the boat, although he was only called a wheelman, because at that time no colored man could have, in fact, been made a pilot. For some time previous he had been watching for an opportunity to carry into execution a plan he had conceived to take the Planter to the Federal fleet. This, he saw, was about as good a chance as he would ever have to do so, and therefore he determined not to lose it. Consulting with the balance of the crew, Smalls found that they were willing to co-operate with him, although two of them afterwards concluded to remain behind. The design was hazardous in the extreme. The boat would have to pass beneath the guns of the forts in the harbor. Failure and detection would have been certain death. Fearful was the venture, but it was made. The daring resolution had been formed, and under command of Robert Smalls wood was taken aboard, steam was put on, and with her valuable cargo of guns and ammunition, intended for Fort Ripley, a new fortification just constructed in the harbor, about two o'clock in the morning the Planter silently moved off from her dock, steamed up to North Atlantic wharf, where Smalls's wile and two children, together with four other women and one other child, and also three men, were waiting to embark. All these were taken on board, and then, at 3.25 a. m., May 13, the Planter started on her perilous adventure, carrying nine men, five women, and three children."

With everyone aboard, Robert Smalls turned the Planter out to sea, towards the blockading Union fleet. They now faced the danger of sailing directly beneath deadly guns of the Charleston harbor batteries:

"Passing Fort Johnson, the Planter's steam-whistle blew the usual salute and she proceeded down the bay. Approaching Fort Sumter, Smalls stood in the pilot-house leaning out of the window, with his arms folded across his breast, after the manner of Captain Relyea [the Planters Captain], the commander of the boat, and his head covered with the huge straw hat which Captain Relyea commonly wore on such occasions.

The signal required to be given by all steamers passing out was blown as coolly as if General Ripley [commander of Charleston's defenses] was on board, going out on a tour of inspection. Sumter answered by signal, "All right," and the Planter headed toward Morris Island, then occupied by Hatch's light artillery, and passed beyond the range of Sumter's guns before any body suspected anything was wrong. ... As the Planter approached the Federal fleet, a white flag was displayed, but this was not at first discovered, and the Federal steamers, supposing the Confederate rams were coining to attack them, stood out to deep water. But the ship Onward, Captain Nichols, which was not a steamer, remained, opened her ports, and was about to fire into the Planter, when she noticed the flag of truce. As soon as the vessels came within hailing distance of each other, the Planter's errand was explained. Captain Nichols then boarded her, and Smalls delivered the Planter to him. ...the Planter, with Smalls and her crew, were sent to Port Royal, to Rear-Admiral Du Pont, then in command of the Southern squadron."

Civil War Service

Upon becoming a free man, Robert Smalls went to work in service of the Union. He was hired to pilot Union vessels in the coastal waters of South Carolina and Georgia. In this capacity, he actively pursued his duty as the report goes on to tell us:

"Captain Smalls was soon afterwards ordered to Edisto to join the gunboat Crusader, Captain Rhind. He then proceeded in the Crusader, piloting her and followed by the Planter, to Simmous's Bluff, on Wadmalaw Sound, where a sharp battle was fought between these boats and a Confederate light battery and some infantry. The Confederates were driven out of their works, and the troops on the Planter landed and captured all the tents and provisions of the enemy. This occurred some time in June, 1862.

Captain Smalls continued, to act as pilot on board the Planter and the Crusader, and as blockading pilot between Charleston and Beaufort. He made repeated trips up and along the rivers near the coast, pointing out and removing the torpedoes [mines] which he himself had assisted in sinking and putting in position. During these trips he was present in several fights at Adams's Run, on the Dawho River, where the Planter was hotly and severely fired upon: also at Rockville, John's Island, and other places. Afterwards he was ordered back to Port Royal, whence he piloted the fleet up Broad River to Pocotaligo, where a very severe battle ensued. Captain Smalls was the pilot on the monitor Keokuk, Captain Ryan, in the memorable attack on Fort Sumter, on the afternoon of the 7th of April, 1863. In this attack the Keokuk was struck ninety-six times, nineteen shots passing through her. She retired from the engagement only to sink on the next morning, near Light-House Inlet. Captain Smalls left her just before she went down...

When General Gillmore took command Smalls became pilot in the quartermaster's department in the expedition on Morris Island. He was then stationed as pilot of the Stono, where he remained until the United States troops took possession of the south end of Morris Island, when he was put in charge of Light House Inlet as pilot."

Black men were not given command of Union boats, so Robert Smalls always worked as the pilot under the command of a white Captain. In late 1863, that state of affairs was changed...

"Upon one occasion, in December, 1863, while the Planter, then under Captain Nickerson, was sailing through Folly Island Creek the Confederate batteries at Secessionville opened a very hot fire upon her. Captain Nickerson became demoralized and left the pilot-house and secured himself in the coal-bunker. Smalls was on the deck, and finding out that the captain had deserted his post, entered the pilot-house, took command of the boat, and carried her safely out of the reach of the guns. For this conduct he was promoted by order of General Gillmore, commanding the Department of the South, to the rank of captain, and was ordered to act as captain of the Planter, which was used as a supply-boat along the coast until the end of the war."

After The War

Robert Smalls was given a prize share of $1500 (roughly $34,000 in 2012) for the capture of the Planter, but that was hardly a fair prize for the value of his capture. The value the US government gave to the Planter when Robert's prize was awarded was $9,000 (roughly $204,000 in 2012).

The Committee on Naval Affairs report discussed the injustice of the award given for the capture of the Confederate gunboat. In the report it was stated that actual value of the Planter was between $60,000 and $70,000 (roughly $1.36-1.59 million in 2012). Despite the Committee's recommendation, Robert was never given any additional reward for his action, and the report summed it up this way:

"It is a severe comment on the justice as well as the boasted generosity of the Government that, whilst it had received $60,000 to $70,000 worth of property at the hands of Captain Smalls, it has paid him the trifling amount of $1,500, and for twenty years his gallant daring and distinguished and valuable services which he has rendered to the country have been wholly unrecognized."

This injustice did not hold back Robert Smalls. After the war he lived in South Carolina, where he served in the State House of Representatives (1868-1870), State Senate (1870-1874), and US House of Representatives (1875-1879, 1882-1883, and 1884-1887).

He remained a leader in his community right up until his death in 1915 at the age of 75. Without a doubt, Robert Smalls was a true Civil War hero, and I think his story is still one of the best stories of the war.

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.